TSUNAMI

Tsunami are natural hazards that are often particularly devastating and can cause extensive damage. But what are tsunami and what should one do in the event of a tsunami? This topic page provides a brief overview of the subject, gives information on early warning, and provides useful links.

© pixabay

What are Tsunami?

Like earthquakes, tsunami are geodynamic natural hazards. The Japanese term tsunami, ‘harbour wave’ in German (ESKP 2020), refers to ‘a wave that is particularly pronounced in harbours and bays and often causes great devastation there’ (GFZ 2015). As a rule, tsunami consist of several consecutive, long-period waves that are generated by the release of sufficient energy and a vertical displacement of water masses. Around 90 per cent of all tsunami are triggered by seaquakes or coastal earthquakes. Other causes can be surface or underwater landslides, volcanic eruptions, collapses of volcanic flanks and landslides (ESKP 2018). Tsunami caused by meteorite impacts and other large cosmic projectiles are very rare, which is why they have hardly been researched to date. Around two thirds of all tsunami occur within the ‘ring of fire’ in the Pacific Ocean, but tsunami can also occur in all other oceans, seas and large lakes (Aktion Deutschland Hilft).

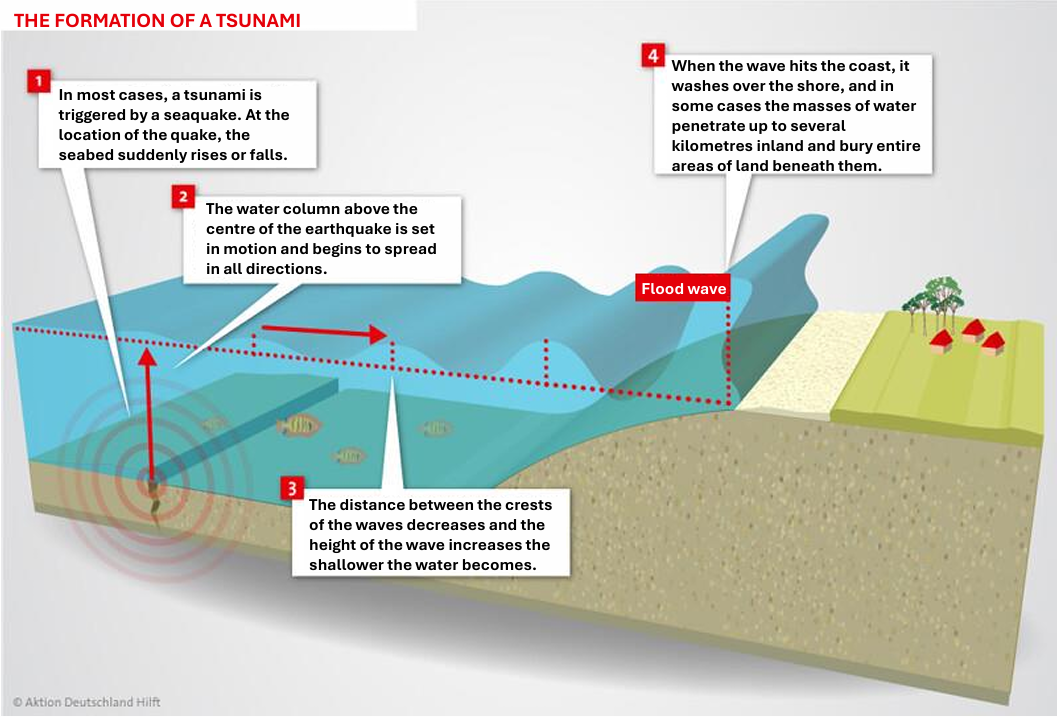

In contrast to wind-generated water waves, tsunami excite the water masses to great depths, often down to the sea floor. As tsunami waves propagate in all directions with typical wavelengths of 500 to 1000 kilometres, they are barely perceptible in the open ocean (Grotzinger & Jordan 2017). The speed and wavelength of a tsunami only decrease with decreasing water depth, while at the same time very large wave heights are generated in some cases. This often makes a tsunami very destructive when it hits the coast (see Figure 1). In addition to the wave height, the energy also plays a role, so that in shallow coastal areas the tsunami waves can often penetrate far inland. The behaviour of a tsunami strongly depends on the coastal morphology. Even in areas far away from the point of origin, tsunami still have a high potential for damage (Aktion Deutschland Hilft).

Figure 1: Development of a tsunami (translated from Aktion Deutschland Hilft)

Tsunami in lakes

Tsunami do not only occur in the oceans and seas, but can also occasionally occur in lakes. Historical events show that Swiss lakes have been repeatedly affected and that lake tsunamis pose a serious danger (ETH Zurich). Lake tsunami can be triggered by submarine mudslides, earthquakes or, above all, landslides. In 1996, for example, smaller waves occurred in Lake Brienz and in 1687 waves over four metres high occurred in Lake Lucerne (University of Bern 2018). The same applies to Norwegian fjords and comparable bays in Alaska, if they are characterised by deep topographical incisions.

Mega-tsunami

Tsunami with a height of hundreds of metres are also referred to as mega-tsunami. Due to the rarity of these events, there is no scientifically standardised definition for the term mega-tsunami (Goff et al. 2014). The highest mega-tsunami ever measured occurred in the Lituya Bay fjord in Alaska on 7 July 1958, when a magnitude 7.7 earthquake triggered a landslide in which a rock about 732 metres long and 914 metres wide and 91 metres thick broke away from the northern wall of the fjord and fell into the bay from a height of about 610 metres (WSSPC). The resulting tsunami reached a height of up to 524 metres on the opposite cliff face. This is still visible today, as the erosion at that time left a clear boundary, which can be seen today in the different vegetation between the older and younger plants (Khan 2013).

Past tsunami events

Japan 2011

On 11 March 2011, the Tohoku earthquake off Japan’s east coast caused a triple disaster with devastating effects. The seaquake with a magnitude of 9.1 triggered a tsunami with a maximum wave height of up to 40 metres, which flooded an area of at least 500 km² (GeoSphere Austria 2021). The Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant was also flooded, leading to a critical nuclear accident in which the reactor building was destroyed and radioactive nuclides were released into the atmosphere and the Pacific Ocean (BASE 2024). In total, more than 18,000 people died. This includes several thousand victims who were never recovered (NCEI 2021). 41 THW task forces from the Rapid Deployment Unit Recovery Abroad (SEEBA) team were deployed in Japan (THW Viernheim 2011). More than 123,000 houses were completely destroyed and almost a million more damaged. Overall, 98 per cent of the damage was caused by the tsunami. The cost of the damage in Japan alone was estimated at USD 220 billion, making the event the most expensive disaster in history to date (NCEI 2021).

Indian Ocean 2004

On 26 December 2004, the Sumatra-Andaman earthquake occurred off the north coast of Sumatra in the Indian Ocean. The magnitude 9.1 seaquake and the subsequent tsunami waves up to 25 metres high caused the destruction of entire coastlines in Sri Lanka, Thailand, Indonesia, India and several East African countries (GeoSphere Austria 2014). Around 230,000 people lost their lives in the disaster, around 110,000 suffered serious injuries and 1.7 million people were left homeless (DWD 2014). The cultural, material and ecological damage was also immeasurable. The total material damage in the Indian Ocean region was estimated at 10 billion dollars, 20% of which was covered by insurance (NCEI 2014).

Tsunami in the Mediterranean Sea

There is also a serious tsunami risk in the Mediterranean, as earthquakes in the region can reach magnitudes of 7.5 to 8, which could generate tsunamis with wave heights of 5 to 6 metres (ESKP). Historical tsunami events in the Mediterranean region have been triggered by strong seaquakes as well as landslides or volcanic eruptions, such as the tsunami at the Stromboli volcano in Italy in 2002 (ESKP 2018). The earthquake in the Strait of Messina in Italy on 28 December 1908 and the resulting tsunami are among the most catastrophic events in history, causing 60,000 to 100,000 deaths and almost completely destroying the cities of Messina and Reggio Calabria (Pino et al. 2000). The tsunami caused devastating flooding along the Sicilian and Calabrian coasts, with wave heights of up to 13 metres and a penetration depth of up to 700 metres inland (Manna et al. 2009). According to UNESCO, there is a 100 per cent probability that a tsunami with a height of at least one metre will occur in the Mediterranean region in the next 30 to 50 years (UNESCO 2024).

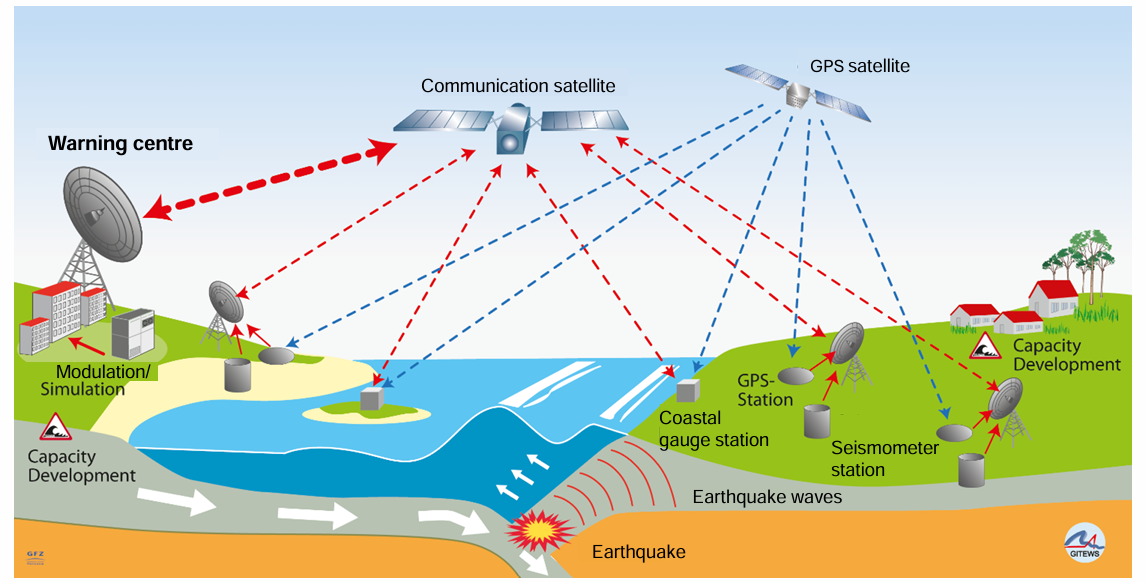

Tsunami early warning

Early warning systems and protective measures are crucial to minimising the damage caused by future tsunami events. Modern measuring methods and early warning systems can locate tsunamis at sea at an early stage and send automatic warnings to authorities and the population so that evacuation measures can be taken in good time (Aktion Deutschland Hilft). An effective early warning system (EWS) is only successful if the affected population groups can both understand the warnings and respond appropriately (UN). How the EWS works is shown in the following diagram.

Figure 2: How a tsunami early warning system works (translated from GFZ)

There has been a tsunami early warning system in the Pacific Ocean since 1968, which was set up by the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC) of UNESCO (Aktion Deutschland Hilft). A comparable infrastructure was not in place in the Indian Ocean at the time of the devastating tsunami event in 2004. One important lesson learnt from the disaster was the urgent need to set up a tsunami early warning system for the Indian Ocean. The GeoForschungsZentrum Potsdam (GFZ) and partners have been intensively involved in setting up such a system in the region. In 2008, the German Indonesian Tsunami Early Warning System (GITEWS) was put into operation (GITEWS 2014). Since the end of March 2011, the Indonesian government has been operating the system completely on its own under the name InaTEWS.

In the meantime, a warning system infrastructure has also been coordinated with the tsunami early warning system for the North Atlantic and the Mediterranean ‘NEAMTWS’ (North-eastern Atlantic, the Mediterranean and connected seas Tsunami Warning System). The group of participating countries, under the moderation of UNESCO’s Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission (IOC), comprises 39 states. France, Greece, Italy, Portugal and Turkey are active as accredited warning services (UNESCO 2023).

Recommendations for action in the event of a tsunami

The tsunami warning system worked in Japan and the circumpacific region during the 2011 disaster, but the tsunami risk was underestimated as the magnitude of the seaquake was initially underestimated. In some regions, many residents relied on breakwaters and other protective measures that gave them a false sense of security. The 2011 disaster in Japan illustrates that tsunami early warning systems and protective measures are not always reliable. It is therefore important to act as quickly and prudently as possible in the event of a tsunami (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: Tsunami sign in Chile: evacuation route (DKKV)

Aktion Deutschland Hilft recommends the following behaviour for private individuals in the event of a tsunami:

Before the event

- Inform yourself in advance about escape routes, evacuation routes, assembly points

Warning signals

- Strong earthquakes or earthquakes lasting longer than 20 seconds

- Rapid rise or fall of water

- Increase in the volume of ocean noise

- Flight instincts or conspicuous behaviour of animals

In risk areas, authorities warn about

- Radio and TV

- Loudspeakers and sirens

- Mobile phone/push messages

During the event

On the open sea:

- Stay on boats or ships

- Get further away from land

On land:

- Warn people nearby

- a Tsunami waves can reach the coast after a few minutes, you should seek shelter on a natural elevation such as a mountain or hill as soon as possible after a strong earthquake

- If there is no natural elevation in the immediate vicinity, climb onto the roofs of stable buildings (do not seek shelter in buildings!)

- If there is no elevation nearby, try to get as far inland as possible, avoiding river valleys and lagoons

- If you are caught by a tsunami, try to hold on to a solid object to stay afloat

After the event

- Stay in a safe place until the authorities give the all-clear

After the all-clear signal

- Search for relatives

- Rescue victims

- Caring for the injured

Created: October 2024

Current Information

No Results Found

The page you requested could not be found. Try refining your search, or use the navigation above to locate the post.

Additional Information

DKKV

Further Links

- GFZ: Fact sheet Tsunami

- GFZ: Tsunami early warning and hazard

- CEDIM: Forensic Disaster Analyses

- CEDIM: Global Tsunami Risk Model

- Quarks: Tsunami in Germany

- ESKP: Tsunami-prone regions in the Mediterranean

Created in October 2024